shifting the silence

Anthea Hamilton, P. Staff, Ghita Skali, Abbas Zahedi. Curated by Giulia Civardi

Anthea Hamilton, P. Staff, Ghita Skali, Abbas Zahedi. Curated by Giulia Civardi

When pronouncing the word ‘above’, the tongue is said to be ‘in neutral’. It doesn’t move, yet it still produces a sound, a shape to the word, an indication: above. There’s an inherent contradiction that comes with associating the ‘neutral’ with something muted, disengaged, or impartial. Even when not involved, something as soft as a tongue can affect the rest.

According to the practice that studies signs and meaning-making, there is a tendency to judge novel stimuli based on the perception of stimuli from the past. Once we see a sky for the first time, a blueprint is produced that will affect how we see other skies, despite their nuances. There is always a trace, a ‘neutral level’, which carries with it meaning. The question is when and how this trace will reveal itself.

Behind a wall in the gallery, in a windowless part of the building, lived a Hausmasta: the historic caretaker of Viennese buildings, who carried out maintenance work and looked after tenants. Living on-site but hidden from others, hausmastas were not meant to be seen or heard. At the same time, they were the eyes and ears of the building, the guarding spirits of the place. This gave them a degree of neutrality; a present absence. What stories could they have revealed?

Reimagining the gallery as a system of traces — ideologies, but also histories and material properties of the building — the project explores various levels at which something or someone ‘neutral’ operates. Bringing together sonic and visual works that embrace minimalist gestures, the exhibition opens a space for re-negotiating identities and othered positions. The artists in the show explore questions of identity and belonging, starting from personal narratives. By switching between various linguistic codes, they shift the perception of what may be considered neutral: unpolluted, unoccupied, silent, invisible, natural - deconstructing and exposing the architectures that shape our bodies and collective imaginaries.

According to the practice that studies signs and meaning-making, there is a tendency to judge novel stimuli based on the perception of stimuli from the past. Once we see a sky for the first time, a blueprint is produced that will affect how we see other skies, despite their nuances. There is always a trace, a ‘neutral level’, which carries with it meaning. The question is when and how this trace will reveal itself.

Behind a wall in the gallery, in a windowless part of the building, lived a Hausmasta: the historic caretaker of Viennese buildings, who carried out maintenance work and looked after tenants. Living on-site but hidden from others, hausmastas were not meant to be seen or heard. At the same time, they were the eyes and ears of the building, the guarding spirits of the place. This gave them a degree of neutrality; a present absence. What stories could they have revealed?

Reimagining the gallery as a system of traces — ideologies, but also histories and material properties of the building — the project explores various levels at which something or someone ‘neutral’ operates. Bringing together sonic and visual works that embrace minimalist gestures, the exhibition opens a space for re-negotiating identities and othered positions. The artists in the show explore questions of identity and belonging, starting from personal narratives. By switching between various linguistic codes, they shift the perception of what may be considered neutral: unpolluted, unoccupied, silent, invisible, natural - deconstructing and exposing the architectures that shape our bodies and collective imaginaries.

8.09.23—14.10.23

GIANNI MANHATTAN, Wassergasse 14, 1030 Vienna

> Installation views

When pronouncing the word ‘above’, the tongue is said to be ‘in neutral’. It doesn’t move, yet it still produces a sound, a shape to the word, an indication: above. There’s an inherent contradiction that comes with associating the ‘neutral’ with something muted, disengaged, or impartial. Even when not involved, something as soft as a tongue can affect the rest.

According to the practice that studies signs and meaning-making, there is a tendency to judge novel stimuli based on the perception of stimuli from the past. Once we see a sky for the first time, a blueprint is produced that will affect how we see other skies, despite their nuances. There is always a trace, a ‘neutral level’, which carries with it meaning. The question is when and how this trace will reveal itself.

Behind a wall in the gallery, in a windowless part of the building, lived a Hausmasta: the historic caretaker of Viennese buildings, who carried out maintenance work and looked after tenants. Living on-site but hidden from others, hausmastas were not meant to be seen or heard. At the same time, they were the eyes and ears of the building, the guarding spirits of the place. This gave them a degree of neutrality; a present absence. What stories could they have revealed?

Reimagining the gallery as a system of traces — ideologies, but also histories and material properties of the building — the project explores various levels at which something or someone ‘neutral’ operates. Bringing together sonic and visual works that embrace minimalist gestures, the exhibition opens a space for re-negotiating identities and othered positions. The artists in the show explore questions of identity and belonging, starting from personal narratives. By switching between various linguistic codes, they shift the perception of what may be considered neutral: unpolluted, unoccupied, silent, invisible, natural - deconstructing and exposing the architectures that shape our bodies and collective imaginaries.

According to the practice that studies signs and meaning-making, there is a tendency to judge novel stimuli based on the perception of stimuli from the past. Once we see a sky for the first time, a blueprint is produced that will affect how we see other skies, despite their nuances. There is always a trace, a ‘neutral level’, which carries with it meaning. The question is when and how this trace will reveal itself.

Behind a wall in the gallery, in a windowless part of the building, lived a Hausmasta: the historic caretaker of Viennese buildings, who carried out maintenance work and looked after tenants. Living on-site but hidden from others, hausmastas were not meant to be seen or heard. At the same time, they were the eyes and ears of the building, the guarding spirits of the place. This gave them a degree of neutrality; a present absence. What stories could they have revealed?

Reimagining the gallery as a system of traces — ideologies, but also histories and material properties of the building — the project explores various levels at which something or someone ‘neutral’ operates. Bringing together sonic and visual works that embrace minimalist gestures, the exhibition opens a space for re-negotiating identities and othered positions. The artists in the show explore questions of identity and belonging, starting from personal narratives. By switching between various linguistic codes, they shift the perception of what may be considered neutral: unpolluted, unoccupied, silent, invisible, natural - deconstructing and exposing the architectures that shape our bodies and collective imaginaries.

A seemingly silent and impartial object such as a squash–a leitmotif in Anthea Hamilton's oeuvre–opens multiple narratives and possibilities of representation. Partly inspired by the characters of the book series ‘The Garden Gang’, written by 9-year-old author Jayne Fisher, Hamilton recurs to vegetables as a subject - but also as a mode of practice that creates a space for joy and potential, syncretic encounters, and new meanings. The glass sculptures carry traces, among the others, of the artist’s childhood memories and peer-to-peer acts of connection with another girl author; references to Art Nouveau organic forms, the 20s and 30s work of artist Maurice Marinot, and the vegetables themselves. Opaque sculptural forms become subtle protagonists against a Scrambled Sky. While setting an idyllic and virtual scenario, the sculptures and wallpaper destabilise the boundaries of the space, calling into question the ideological constructs of the gallery itself and introducing other hybrid environments.

Moving between architecture and landscapes, Ghita Skali’s two-part video Palm Attacks examines how a common date palm, the Phoenix Dactylifera, takes on unexpected functions. Two fictional characters in the film, a tour guide and an economist, reflect on the evolving role of the palm tree in Morocco. Once a symbol of the ‘exotic’, palm trees are now often turned into cell towers, their foliage laced with receptors, to meet the demands of advancing technologies. Meanwhile, Skali’s series of photographs Montessori is has been captures the facades of private schools in Morocco. Named after predominantly white male figures, such as Steve Jobs and Walt Disney, and using French and English, the schools carry ongoing traces of Western colonial influence. By framing images with white borders that allude to the strategies of canonical black & white landscape photography, Skali exposes the tools that shape urban and social fabrics in Morocco, inviting reflections on the implications of neutralising the ‘Global South’ and its effects on its education systems.

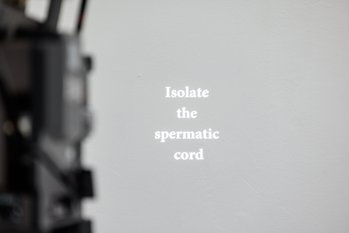

Exploring language from a somatic perspective, P. Staff’s 16 mm film Depollute interrogates what may be considered natural for some, while a toxic presence in the body for others. The silent, two-minute film presents a set of clinical instructions required to perform a self-orchiectomy (the surgical removal of one or both testicles). Capturing the viewer with pulsating words and colours, the fast-paced work explores self-surgery as a form of bodily autonomy and self-actualisation, while also a complex and possibly harmful procedure. In this way, Staff’s film reminds us of the ambivalent relationship between the medical industrial system, harm, and care.

Abbas Zahedi’s work 11:11 (1030) offers a remapping of space through sound, sensory elements, and minimal gestures. Barely visible pencil lines demarcate the entryway of where the Hausmasta apartment used to be. Meanwhile, elusive sounds emerge from small apertures in the space–a hole in the wall, a ceiling window–all connected via audio cables. The sounds are composed using flooring tiles previously found in a sorting office in South-West London, where Zahedi presented Ouranophobia, a collaborative exhibition accessible only to people working on the front lines of the pandemic. In this new iteration of the project, Zahedi uncovers the past lives of the gallery building, connecting us with different layers of space (the material and secular, but also atmospheric and psychological). Drawing from common materials and the therapeutic, spiritual, and meditative practices where sound facilitates the release of pain and grief, the work carries the potential for a more emotional attunement while opening multiple entryways into personal narratives. As Zahedi asks, referring to the Ouranophobia as signifying ‘fear of the sky’: ‘How do I develop a sense of place in the cosmos when all I can rely on is the ground beneath my feet?’. Staircases, exit signs, and floor tiles forming an arrow propose multiple exits. And yet, they bring us back to the same space where we began: at a ground level.

Rather than a way out, the exhibition proposes the possibility to inhabit and view structures from different perspectives, inverting grounds and skies; an invitation to sense a way through the silence, between what is not seen or said. If neutrality, by temporarily suspending terms and categorisation, can open a third space for negotiation, who can speak and be silent? Who is there to hear?

Abbas Zahedi’s work 11:11 (1030) offers a remapping of space through sound, sensory elements, and minimal gestures. Barely visible pencil lines demarcate the entryway of where the Hausmasta apartment used to be. Meanwhile, elusive sounds emerge from small apertures in the space–a hole in the wall, a ceiling window–all connected via audio cables. The sounds are composed using flooring tiles previously found in a sorting office in South-West London, where Zahedi presented Ouranophobia, a collaborative exhibition accessible only to people working on the front lines of the pandemic. In this new iteration of the project, Zahedi uncovers the past lives of the gallery building, connecting us with different layers of space (the material and secular, but also atmospheric and psychological). Drawing from common materials and the therapeutic, spiritual, and meditative practices where sound facilitates the release of pain and grief, the work carries the potential for a more emotional attunement while opening multiple entryways into personal narratives. As Zahedi asks, referring to the Ouranophobia as signifying ‘fear of the sky’: ‘How do I develop a sense of place in the cosmos when all I can rely on is the ground beneath my feet?’. Staircases, exit signs, and floor tiles forming an arrow propose multiple exits. And yet, they bring us back to the same space where we began: at a ground level.

Rather than a way out, the exhibition proposes the possibility to inhabit and view structures from different perspectives, inverting grounds and skies; an invitation to sense a way through the silence, between what is not seen or said. If neutrality, by temporarily suspending terms and categorisation, can open a third space for negotiation, who can speak and be silent? Who is there to hear?